Japanese Potteries(Explanations to the technical terms of ceramics No.18)

There are various technical words on potteries. Here are some of those, for which I'd like to give you some remarks.

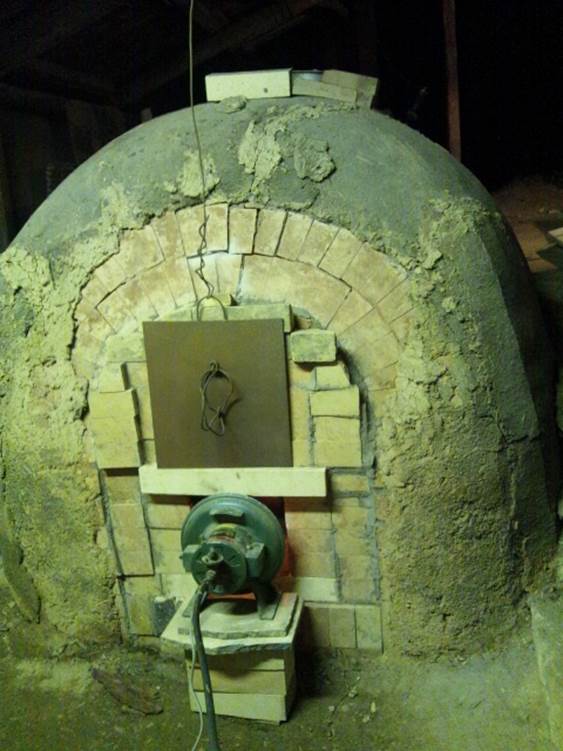

Anagama (and Kiln Firing)

Anagama (and Kiln Firing) An anagama is the pottery cave kiln that is built in a tunnel shape slightly sloping upward, which inside space becomes narrower gradually from the entrance to the deep end that leads to the flue. It can be mentioned, from its very simple structure, as the original form of a pottery kiln that is fueled with firewood. The anagama seems to be one of those handed over from the Korean Peninsula in the 11th century together with the Sue ware and the technique of potter’s wheel. It tends to have a gap of inside temperature and its thermal efficiency is low, however, the anagama would be a kind of kiln that creates interesting variation of tastes by ways to place works inside and that is suitable to produce potteries with rural beauty.

Complete view of anagama, approx. 3 meters in length

I attended a friend of mine who was a ceramic artist when he went to an anagama site to fire his works. Here I like to report the whole process from its preparatory works through ignition, aburi (initial firing in a lower temperature) and firing up to ending.

Preliminary Arrangement:

Firewood is the fuel for an anagama. You should receive it from the supplier no later than half a year before using to make it sufficiently dried up. At first, you arrange all the bundles of more or less 5 wood pieces each in parallel crosses and leave them outdoor with tin plates to cover the whole blocks over. If possible to manage, you’d better remove the tin plates in every sunny days. Then, about 3 months before using, you bring all the woods inside the building to avoid any contact with rain. If a wood piece is well dried, it clangs lightly in a high-pitched tone of sound.

This place of the anagama, deep in a mountain, is surrounded by nature and so comfortable. However, it becomes not easily accessible because of infested weeds in summer, so it is also an important work to trim those weeds so that the fresh air flows sufficiently to the firewood.

A view of the kiln site, after moving firewood to the space under the roof

Repair Works on the Kiln:

It was necessary to check the whole part of the kiln because 2 years went by after it was last used. We were to fix every damaged part by ourselves. First of all, we peeled off kamatsuchi (fire clay, or also called as dosembo) used in the previous firing. Kamatsuchi is a sandy clay to be used in the gaps between tsuku (props to arrange shelf plates) and the shelf plates or to prevent works from sticking to the kiln floor, which is good to be used as a material in a kiln as it’s so sandy and doesn’t get tightened in fire. We peeled off the kamatsuchi stuck to tsuku or bricks paved over the kiln floor with using chisels. In the deeper area inside the kiln, it could be easily peeled off, but in the front area around the origin of fire, the ash melted and vitrified over kamatsuchi or some broken works stuck to the floor, where something like chisels were useless and we used disk grinders to peel it off properly. But we still had to change some bricks which surface was covered by unpeelable glassy stuff. In fact, we didn’t want to do this work to change bricks because, for that, we needed to make all the bricks around the area apart by cutting the paste between the bricks which was a terribly hard job, which should really be a final solution. We had no choice at that time, however, for avoiding such situation, it would be the principle to place durable works produced with highly heat-resistant clay only nearby the origin of fire.

Likewise, kamatsuchi or melted clay stuck to shelf plates must be peeled off properly with using chisels or disk grinders.

A view of the kiln site, after moving firewood to the space under the roof

Kiln Stuffing:

That kiln is as long as 3 meters, which is the length that can be sufficiently fired by feeding firewood only from its front. It is a shorter type for anagama, but still there may be a gap of temperature inside the kiln that is more or less 100 degrees Celsius and the mood or taste of potteries fired by the kiln will be totally different depending on the location to be placed. Therefore, where to place a work is determined by the desired taste.

In the front area of the kiln, you can make potteries in bright yellowish green or yellow with a glossy texture due to plenty ash scattered over—not over the whole part of works but only over a single side facing to the fire hall, which naturally makes different expressions of the pottery’s surface by whether it’s front or back toward the fire. The backside will usually have a slightly rough atmosphere with ash not being completely melted. This is the interesting aspect of firewood kilns, which can’t be enjoyed if electric or gas kilns. By the way, there is a way, called korogashi (leaving it turned over), that you lay a work down nearby the fire hall, where plenty ash will be piled up over and will take effect to create an interesting expression of the work. This may be described as a double-or-nothing way to stuff the kiln expecting it to be colored unimaginably, depending on a degree of deoxidation or a volume of ash piled up, in the complicated mixture of grey, pink, purple, brown, etc. that can’t be easily produced artificially.

In the right middle to the deeper end of the kiln, you can aim for making it rather in scarlet color. Unglazed white clay will respond to the alkalinity of firewood when fired through and the color will turn to be orange or red. There is another way, called hidasuki, which makes clay respond to the alkalinity of straw by wrapping it with straw when firing, however, in this case, the colors like orange or red will be developed only at the part in contact with the straw. On the other hand, the part where scarlet color will be developed with the alkalinity of firewood will be changed greatly depending on kiln stuffing, from which, there is one of attractions about anagama in stuffing it with works estimating the path of fire going through.

You put a dosembo (fire clay) shaped in doughnut-like in the both ends of tsuku (props), on which you set shelf plates measuring their levelness with a level gauge. If this process is conducted without carefulness, it will end up in the shelves being collapsed in the course of stuffing or firing. Really cautious work is required here. Then, you fix 3 to 8 pieces of dosembo shaped like 1-cm-in-height triangular pyramid at the bottom of every individual work in order to make the gap between the work and the shelf plate. The dosembo pieces can be used when stacking works. Sometimes they use shells filled with dosembo clay to be put at the bottom of works. By doing so, the bottom of the pottery will be partially colored in orange due to the salt content of the shells, which becomes an unique view or character of the pottery created by such an extra process.

The deep end of the kiln has been stuffed with works. The lower right is a level gauge.

After the kiln stuffing is finished, you close the entrance of the kiln keeping a fire hall open. Then, you proceed to the aburi process. Aburi is a way of initial firing to gradually remove the humidity contained in the works or in the kiln itself not in a very high temperature immediately but in a lower temperature, adding heat little by little by burning a piece of big log or putting a gas or kerosene-fueled burner inside for half a day.

Gradually adding heat with a kerosene-fueled burner

If you fire the kiln with a strong firepower right after you finished the kiln stuffing, the risk will become higher causing the works to be cracked or the glaze in the surface of works to go off due to the rapidly raising heat. Aburi is a work that requires time and patience. Actually we spent 2 days for the aburi process in the kiln firing at that time for the temperature to reach 800 degrees Celsius. It is important to heat the bricks or the floor of the kiln rather than the works at this stage so that the temperature can be evenly and smoothly raised up in the later stage. Aburi is like a kind of warm-up exercise.

Kiln Firing:

After the kiln stuffing is finished, you close the entrance of the kiln keeping a fire hall open. Then, you proceed to the aburi process. Aburi is a way of initial firing to gradually remove the humidity contained in the works or in the kiln itself not in a very high temperature immediately but in a lower temperature, adding heat little by little by burning a piece of big log or putting a gas or kerosene-fueled burner inside for half a day.

Temperature goes beyond 1200 degrees Celsius and flame starts to blow up from the flue.

The temperature will reach 1300 degrees Celsius.

We tackle the hard work of the kiln with wearing a towel to protect the head as well as sunglasses, leather gloves and an apron, fully protected. If the kiln has a tall flue, it absorbs air very well and gains the temperature up to 1260 degrees easily, just by opening the grate to feed more oxygen into the kiln and increasing the number of firewood. However, the temperature can’t go up further merely by throwing more wood pieces into the kiln because the thermal storage in the kiln is not enough. So, we gather more and more charcoals burning red around the fire hall to gain higher temperature throwing more pieces of firewood in every 10 minutes which is a shorter interval than before, and raise up the combustion efficiency by stirring charcoals with a long pole in every few hours to splash it over the works and to let it be in contact with more oxygen. The terrible heat comes when stirring charcoals with a long pole. The stainless pole becomes red and the hands get almost burned. However, the job must be done very carefully not to hit and break any works with the pole, looking inside the kiln with aplomb in spite of the heat. Flame in the kiln emits white light and we realize that the temperature comes to 1300 degrees. A wood piece turns to be charcoal in a very moment being thrown, and the sound around the fire hole absorbing air becomes stronger. The kiln expands with the heat and a big crack appears on its outer mud wall surface. We feel like we are rearing a living creature having violent heat and light, with astonishment on what a hard work it is to produce potteries.

We pick up a color sample from the kiln to ensure that the ash is melted and the clay gets tightened enough, and stop the fire. The timing to stop the fire is always a worrisome issue, but the deciding factor is the brilliance of color or the firmness of clay. We shut down the fire hall, insulate the flue, and close all of the opening sections by applying clay. As soon as the flue is insulated, flame blows out of every opening part of the kiln and black smoke fulfills, therefore, we stop it by applying clay quickly, and the firing work continued as long as 5 days is over.

the kiln stuffing is finished, you close the entrance of the kiln keeping a fire hall open. Then, you proceed to the aburi process. Aburi is a way of initial firing to gradually remove the humidity contained in the works or in the kiln itself not in a very high temperature immediately but in a lower temperature, adding heat little by little by burning a piece of big log or putting a gas or kerosene-fueled burner inside for half a day.

he fire hall and every opening sections have been closed with bricks and clay.

As I mentioned earlier, anagama is a type of kiln which structure is so primitive. However, I realized from the firing experience that such a simple structure is yet containing a lot of reasonable mechanisms. The kiln that can gain such high temperature without collapsing is not able to be developed by stacking bricks offhand without any knowledge. People who have gone before us had produced variety of masterpieces and fired innumerable pieces of dishware for daily use with this type of kilns. I think that firing anagama today is meant to be an attempt to learn new through visiting old. Physically feeling and absorbing the vanishing wisdom of ancestors, we may find out a path that is leading to more attractive pottery integrated with the modern sense and possibility.